Digby Hildreth reports on the anniversary of ‘the rehab up the road’. Bill B had been through five rehabs before he arrived at The Buttery in the middle of last year.

The son of Vietnamese refugees had been a heroin user for 25 years, since smoking it with his peers in the southwest of Sydney as a young teenager, then using it more frequently to come down after increasingly lengthy ‘weekends’ of partying and recreational drug taking. In time it became the centre of his life, costing him $1000 a day.

Against the stereotype image of a drug addict, Bill (not his real name), maintained a demanding job throughout his adult years, and never injected – both of which he says contributed to an illusion of control and even respectability, and prolonged his using time.

In every other way, Bill typifies the addict’s experience: powerlessness, obsession and compulsion, secrecy and deceit; the camaraderie of the early days on the streets of Cabramatta replaced by isolation and an inability to maintain or invest in relationships.

Nobody knew what he was up to. Not his parents, brother or workmates – another quirk of addiction; as long as its hidden, your own little secret, then you feel as if you’re somehow getting away with it, he says.

But it was unsustainable: the quantities he needed soared, way beyond his earning power; his work started to suffer and the ducking and diving became exhausting.

Bill went into one rehab after another, sometimes trying to ease the horrors of withdrawal by smuggling in his own secret stash – on one occasion cocaine, on another Suboxone (an opioid blocker).

After one of the worst withdrawals of his life – lying on the shower floor with the water pouring on him, racked with vomiting and diarrhoea – he committed to heading north to Binna Burra, way outside of his comfort zone, to the warm embrace of The Buttery.

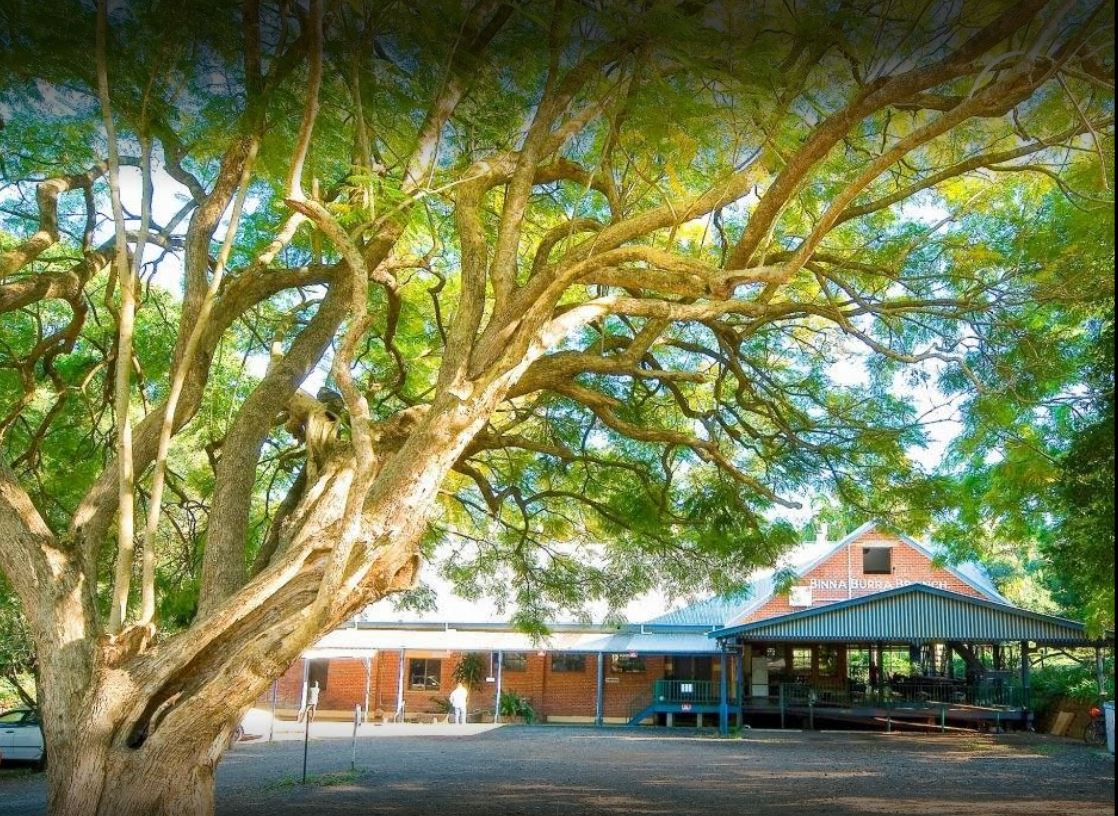

‘The Butt’, much loved in recovery circles in the Northern Rivers and beyond, and fondly known as “the Rehab up the road”, turns 50 this year, a remarkable achievement for an institution that deals with some of the most misunderstood and shunned members of society – and some of the most difficult to treat: alcoholics, addicts of every description, and people suffering mental illness.

In that time, The Buttery has gone from a visionary Christian’s idea of a haven for troubled young people, a drop-in refuge based on kindness and few rules, to a sophisticated therapeutic community with clear, firm expectations and boundaries, offering a range of programs adopted to fit the ever-changing climate of substance use and mental health.

“We haven’t stood still,” says the current CEO, Leone Crayden, “and sadly there is still a great need for our services.” Way more in fact than in 1973. “There are 90 people on the waiting list at present,” Leone says – in a world in which one day’s delay can mean the difference between life and death.

And while alcohol abuse remains the problem it was 50 years ago, the drug scene has changed wildly, especially since the emergence and widespread uptake of methamphetamines and cocaine.

The Buttery is evolving to meet these changes. In September a post-custodial program will be introduced, and the mental health assistance is ever expanding, with a new drop-in service available seven days a week from 10-6. A doctor is on hand 12 hours a week to offer clinical guidance.

An advisory group consisting of those with lived experience of addiction and recovery, people such as Bill, is in the pipeline.

There is a very diverse board, Leone says, made up of both local people and those from interstate. Although it receives $14 million a year in government grants, it relies on community support and couldn’t survive without it. Leone praises the sympathetic people of the surrounding towns and villages: “It is a true community organisation,” she says.

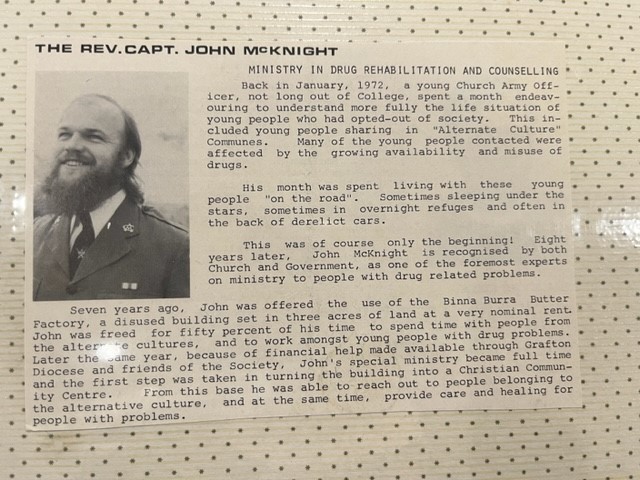

The Buttery was the brainchild of a visionary Church Army Officer named John McKnight who had a position at Bangalow All Souls Anglican Church. He saw a need for youth services following the influx to the region of young people following the Aquarius Festival, and imagined a Christian community offering refuge and support to those who needed it.

When the old butter factory was offered to him in 1973 he accepted it and moved in.

By 1976, thousands of people were staying every year – often itinerant, drug affected, troubled – proving a colossal strain on Infrastructure and resources.

The need for a more focussed purpose became apparent, and the decision was made to provide a therapeutic community with the specific task of treating drug dependence.

A second accommodation unit was built and staff employed with specific drug counselling skills.

Group therapy was introduced in the 80s and a program developed with rules and guidelines. Behavioural, moral and ethical boundaries became more clearly defined.

The emphasis on Christian beliefs was replaced by the spiritual program found in the 12-Step program laid out by Alcoholics Anonymous and adopted since by dozens of other fellowships helping with myriad addiction disorders.

Aftercare became a consideration, so “graduates” were able to move into one of two half-way houses in Byron Bay and start a normal life in mainstream society while supported by others in recovery and community networks such as Narcotics Anonymous.

Today, residents at The Buttery embark on a standard program involving group and individual therapy and education, living skills instruction and stress management training, art therapy and orientation to the ‘12 Step’ philosophy.

Bill is one of 2500 residents offered these healing services this year and like many of them, he was initially untrusting, reluctant – perhaps unable – to know and express with any honesty how he was feeling, what his true thoughts were.

Honesty, willingness and open-mindedness are the key ingredients in a therapeutic community, and Bill learnt how to practise these. The result is he is on his way to becoming a useful, productive member of society. He regularly returns to The Buttery now, to give back, by sharing his experience and wisdom with residents. He will be part of the anniversary celebrations this month.

The past can be healed: Bill tells of his brother driving his aged parents up to visit him – of his father’s habitual hardness dissolving in a hug – and his own ability to be present for them now.

There’s a long way to go, but the transformation is well under way: the gilded cage of a high paying job has lost some of its power; Sydney itself is not so alluring. He is happy now to take time to discover who he really is.

Leone Crayden emphasises that not everyone who comes to The Buttery stays. People drop out, for a host of reasons. “Some people’s lives have been lost,” she says.

Amidst the anniversary celebrations there will be a moment of silence for those who passed through the doors but either left early or couldn’t maintain recovery and died.

Those who come to The Buttery and stay have a better chance than most.